During the four years it took me to write my first novel, the world seemed to end nine times over.

There was a pandemic, a national uprising against racist policing, Russia invading Ukraine, an insurrection against a democratic election, a genocide playing out in real-time on social media, and of course the smallest sampling of what climate change has in store for us in the future: epic wildfires, flooding, extreme heat, tornados, drought, etc.

Many nights I have lain awake during the past five years, red eyes lit up by blue light, thinking:

The world is falling apart and I waste my days writing stories and articles that nobody reads.

This is a concern so many writers share:

I’ve spent years agonizing over this problem. And I haven’t found an answer. But what I have found is a problem with the problem.

First, the problem itself — Is writing the best possible way to save the world? — is just a retelling of American ambition and imbalance. It implies that any one of us could single-handedly change the world (we can’t) and that writers spend their whole days writing. This is unequivocally not true.

Almost all the writers I know spend between 45 minutes to 2 hours a day writing. Listen, I know people who go to the gym for 2 hours every day! And they don’t lie awake at night thinking that they should have been out marching in the streets instead of doing those kettlebell squats. So, the problem itself is a false equivalency. You can write and also try to save the world.

You can write and also try to save the world.

The second problem with the problem is that it takes this very corporate concept of ROI and applies it to giving a shit. We don’t give a shit in linear form. Giving a shit is not an engine and you put in four gallons of tears or sweat or minutes and it spits out a better world.

I once interviewed a bunch of writers for an article about the impact of climate fiction. And almost all of them said some version of:

I am not just writing a book about an issue, I am adding to a conversation that will go on long after I die.

Which is to say, ROI is likely not the appropriate yardstick by which we should measure the impact of our writing. Remember, it’s this kind of black-and-white equation that got us into the climate crisis in the first place. And what seemed like excellent ROI to Exxon in 1980 turns out to have been a very poor trade-off in the rapidly warming world of 2024.

This kind of “cost-benefit analysis” type of thinking about the climate crisis is part of why I created the concept of a climate shadow. When we free ourselves from what can be calculated, we find that what can’t be calculated — like art! — really does have a chance at changing the world. The incredible thing about writing is that there’s no ceiling to the amount of impact it can have.

But the first step is, of course, to write.

I am not just writing a book about an issue, I am adding to a conversation that will go on long after I die.

Now, the third problem with the problem: we act as if we have a choice. And by that, I mean that we pretend we are not compulsively driven to create (I can’t speak for you, but I certainly could not stop writing if I tried), and we pretend that we control the amount our falling-apart-world influences our writing.

In her book of essays Like Love, Maggie Nelson writes that whether or not we are writing directly about the world falling apart, “all the art we are creating now will likely appear suffused — if not to say gaslit — by the slow-burning anxiety created by the deepening climate crisis, and the wealth gap that is its intimate companion.”

Not only is that perhaps the best climate pun I’ve ever come across, but she’s right. We are not separate from the news. Our stories do not exist outside of the context of the feeling of being on a ship that is slowly sinking. Even if you’re writing about the sights. Heck, especially if you’re writing about the sights.

It’s all circular. The writing helps us. It helps us stay curious, stay present, stay excited. It helps others, in ways big and small, in present time and in future worlds we can’t even imagine. The work helps our anxiety, and our anxiety helps the work.

The writing helps us. It helps us stay curious, stay present, stay excited. It helps others, in ways big and small, in present time and in future worlds we can’t even imagine.

And when we finish our writing session and go engage with the world — the complicated, troubling, delightful world — that also helps us. And others. And it helps our writing.

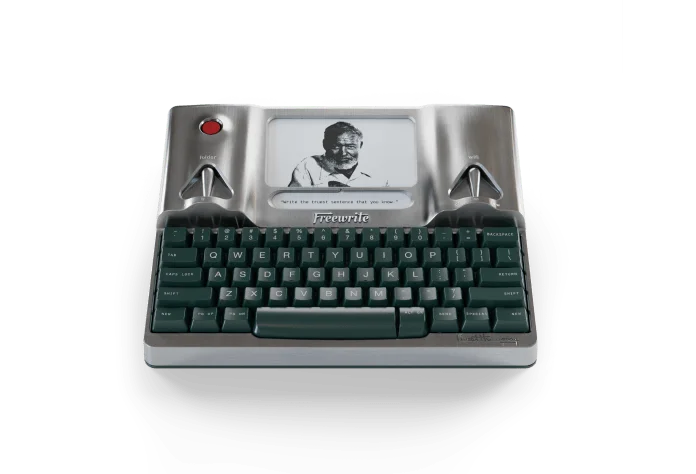

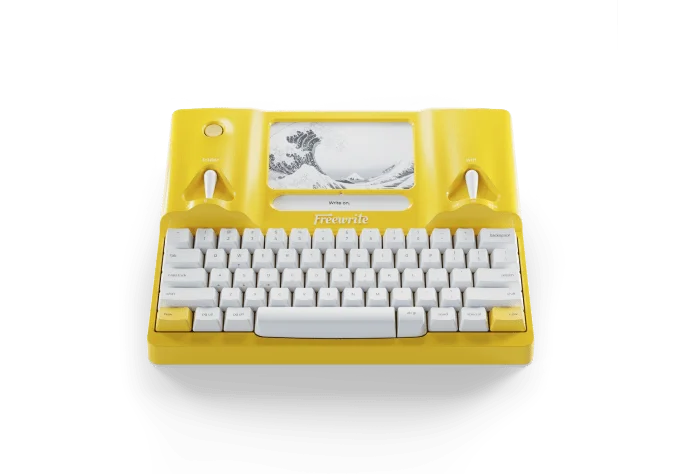

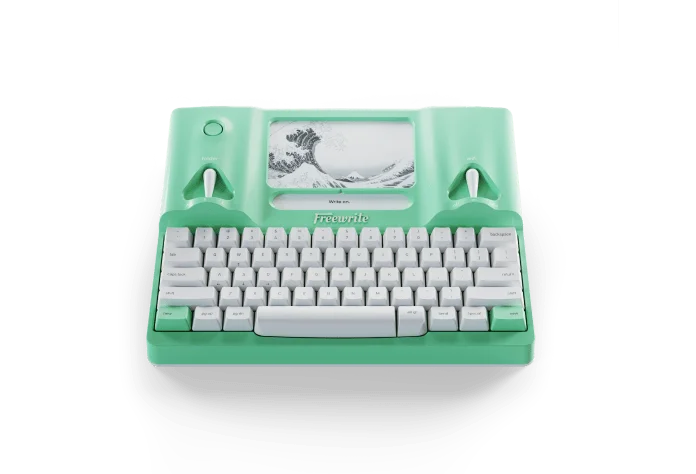

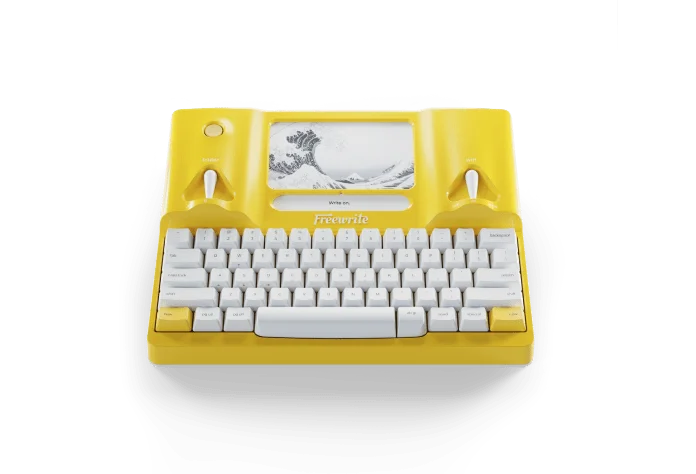

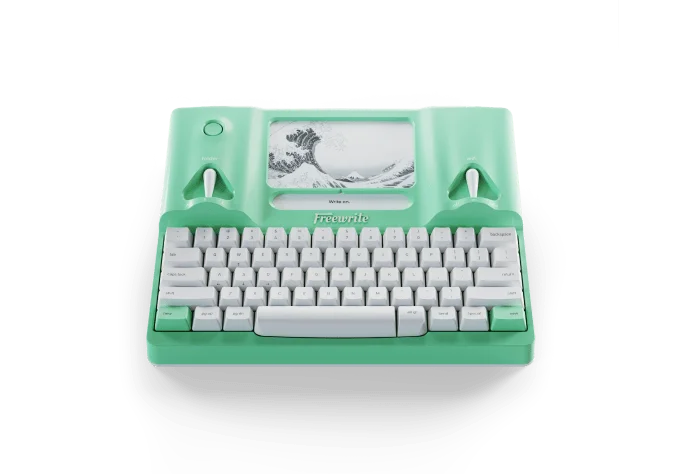

Any moment we are staring the issues straight in the face — whether at a city hall meeting, on the screen of our preferred writing device, marching in the streets, as social media activists, or in the voting booth — we are awake. That is all we can ask of ourselves and each other. To be awake.

The other day, I was leaving a yoga class and I mentioned something about having a big deadline waiting for me at home. The teacher asked what I do and when I told her I was a climate journalist, she said, “You must cry yourself to sleep every night if that’s what you do for work.”

“No,” I replied. “The work is the reason I don’t cry myself to sleep every night.”

Take heart, the reason you care is because you care. What makes you concerned about the world is also what makes you a great writer. It’s the reason your thoughts and ideas are worth reading. The reason you want to put down your writing and do something more altruistic is also the reason you must keep writing.

What makes you concerned about the world is also what makes you a great writer.