Rhetorical devices — which you might hear being referred to as persuasive devices or rhetoric — are commonly used by politicians when they’re trying to encourage you to vote for them in elections. However, rhetoric doesn’t just belong in the political arena. You find rhetorical devices being used in sales pitches and novels in equal measure.

If rhetoric is about persuading you about something (or to do something), why would it be useful in novels? After all, you’re not trying to persuade people when you’re writing a novel...or are you?

In fact, you are. Writing a novel is about persuading your readers to keep reading, convincing them that your story is worth finishing, that your characters and plot-line are worthy of their attention. There’s power to be found when you can harness rhetorical devices in your writing!

Types of Rhetorical Devices — Plus Examples of How They’re Used

Rhetoric was something that the Ancient Greeks identified — so the types of rhetorical devices have some pretty quirky names. The Ancient Greeks split rhetoric into four categories, according to how the devices are designed to appeal to people:

- Logos —an appeal to logic (otherwise known as reason), which tends to use facts and statements

- Ethos —an appeal to ethics (or establishing credibility) so as to be taken seriously as an authority

- Kairos —an appeal to time (or convincing a person that now is the time for a particular action or belief or idea)

- Pathos —an appeal to emotion — such as invoking sympathy or inciting anger

Some rhetorical devices fit into more than one category, however, so categorizing them isn’t as important as knowing how to best use them in your writing!

There are hundreds of rhetorical devices. Some of them you may have heard of —- others you almost certainly won’t have! Don’t worry, I’m not going to bore you with a full list of them. Instead, I’ve selected my personal top eight rhetorical devices that add the power of persuasion to your writing.

1. Anacoluthon

This is a rhetorical device that forces readers to challenge their assumptions. The Ancient Greeks saw it as a means of forcing people to think more deeply about a topic, often during a debate, but it’s just as effective in fiction. A classic example can be found at the very beginning of Kafka’s Metamorphosis:

When Gregor Samsa woke up one morning from unsettling dreams, he found himself changed in his bed into a monstrous vermin.”

2. Accismus

Have you ever pretended that you didn’t want something — or even refused to accept — something that you really want? Feigning indifference to something that you desire is called accismus. An example of this can be found in Aesop's fable of the fox and grapes:

“Driven by hunger, a fox tried to reach some grapes hanging high on the vine but was unable to, although he leaped with all his strength. As he went away, the fox remarked 'Oh, you aren't even ripe yet! I don't need any sour grapes.' People who speak disparagingly of things that they cannot attain would do well to apply this story to themselves.” —Aesop’s Fables

3. Aposiopesis

This rhetorical device is the literary version of trailing off without finishing your sentence to leave listeners (or, in the case of novels, readers) guessing what you were going to finish with. It can get frustrating if you use it too much, though! Shakespeare, in particular, was quite fond of it:

“This is the hag, when maids lie on their backs,

That presses them and learns them first to bear,

Making them women of good carriage:

This is she—”

- Romeo & Juliet,William Shakespeare

4. Bdelygmia

Don’t ask me how to pronounce this one — it makes me think that whoever translated this from the Greek got bored and started stringing letters together, or was hitting the medicinal wine a bit too hard. And, ironically, that last sentence is an example of the device in action! Bdelygmia is simply a stupid word to describe a rhetorical insult. Understandably, Dr. Seuss loved it almost as much as I do:

"You're a foul one, Mr. Grinch, You're a nasty wasty skunk, Your heart is full of unwashed socks, your soul is full of gunk, Mr. Grinch. The three words that best describe you are as follows, and I quote, ‘Stink, stank, stunk!’"

- How the Grinch Stole Christmas, Seuss

5. Asterismos

Hey, this rhetorical device is a simple matter of inserting an attention-grabbing word or exclamation point at the beginning of a phrase — with no purpose other than to grab attention. (You see what I did there? Did it grab your attention?)

It keeps your readers focused on the page, and it’s used a lot in Moby Dick:

“Book! You lie there; the fact is, you books must know your places. You'll do to give us the bare words and facts, but we come in to supply the thoughts.”

- Moby Dick,Herman Melville

6. Anadiplosis

If you want to convince your readers that the logic of what you (or your characters) are saying is flawless, then anadiplosis is the technique you should be using. It uses the same word at the start of one sentence as was at the end of the previous sentence. It creates a kind of chain of thought that guides your reader to concluding that you’re right. For all the Star Wars fans out there, here’s a perfect example:

Fear leads to anger. Anger leads to hate. Hate leads to suffering.”

- Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back.

7. Zeugma

Want to make sure your readers are paying attention to every word you write? Throw in a little zeugma. This rhetorical device is where you create a list out of things that you wouldn’t commonly put together, following a word or phrase that can apply to all items on the list, but in different ways. In the examples, below, the word/phrase that precedes the list is underlined:

Miss Bolo…went home in a flood of tears and a sedan chair.

- Pickwick Papers, Charles Dickens, “

He carried a strobe light and the responsibility for the lives of his men.

- The Things They Carried, Tim O’Brien

In the Dickens example, Miss Bolo’s distress is juxtaposed with her mode of transport — both of which she could go home in. Likewise, O’Brien uses zeugma to juxtapose something that can be physically carried with something that is non-literal in nature.

8. Cacophony

The rhetorical equivalent of banging pots and pans together outside your roommate’s door at 4 in the morning, cacophony is when you deliberately put words together that sound really bad in close proximity to one another. Why would anyone want to do that? Well, ask Lewis Carroll, because he went to the trouble of literally inventing words to create a particularly bad Cacophony. It works — just look:

“’Twas brillig, and the slithy toves

Did gyre and gimble in the wabe:

All mimsy were the borogoves,

And the mome raths outgrabe.”

- Jabberwocky, Lewis Carroll

Why You Should Embrace the Art of Rhetoric

Do you want your readers to be unable to put your book down? Yes? Then that’s the only reason you should ever need to embrace the art of rhetoric. However, if you need more convincing (really, having your readers glued to your book isn’t enough?) then some other great reasons include…

No, really, I’m not going to give you any more reasons. You don’t need them. What you do need is a bunch of rhetorical tools in your writer’s toolbox. I’ve only given you eight here, but there are hundreds of them. Go and hit up your old friend Google and compile yourself a list of the tools that you’d like to try out — and then try them out!

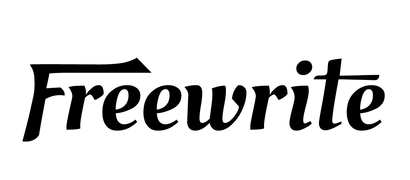

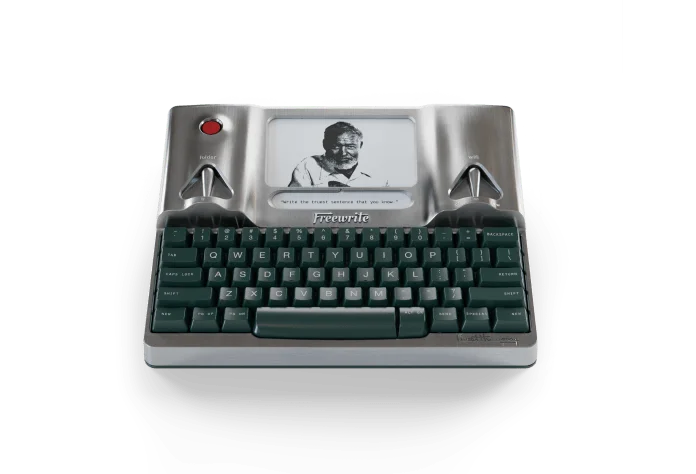

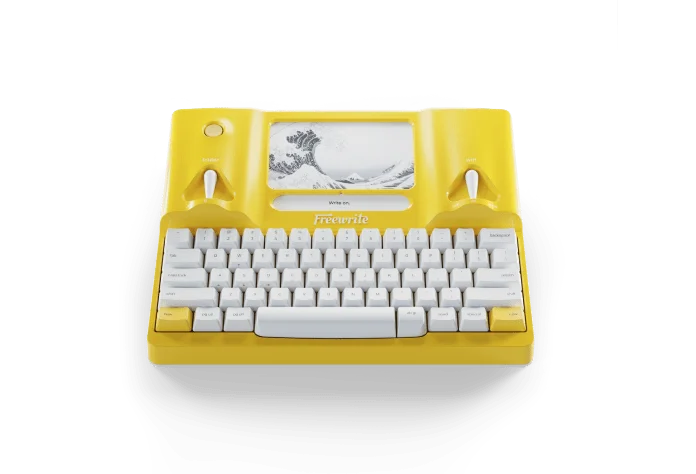

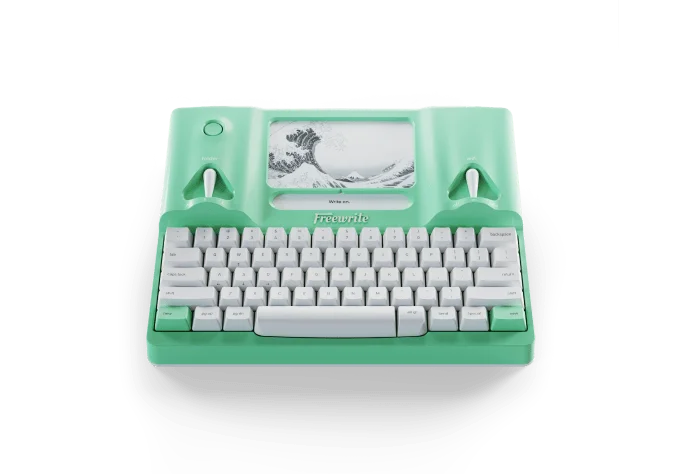

Thankfully, you don’t have to be able to spell or pronounce rhetorical devices in order to be able to use them. Some devices will work better in some types of writing than others, and some may not work for you at all. However, the only way to find out is to try them… so what are you waiting for? Go! Put pen on paper (or fingers on Freewrite keys) and discover the art of rhetorical writing.