Today’s guest post is by editor and author Susan DeFreitas (@manzanitafire), whose debut novel, Hot Season, won the 2017 Gold IPPY Award for Best Fiction of the Mountain-West.

Based on the encounters I’ve had as an author and an editor, I’d say it’s rarer to find someone who doesn’t want to write a book than someone who does.

Many dreamers never so much as start. But there are also a whole lot of would-be authors who start writing a book and never find a way to finish it.

Some writers lose the thread of a novel because they lack a sense of the big-picture, the story as a whole.

Some abandon their writing projects because they lack the discipline to set aside time to write.

But there are many writers who fail not because they’re not cut out for writing, but because they are, in as much that they’re perfectionists. But that perfectionism has been misplaced.

Which is why I consider the idea that you should revise while you’re drafting a book the most dangerous myth about writing.

The Great (Unwritten) American Novel

In 2000, the ink on my degree in creative writing was not yet dry, but I was working on the Great American Novel.

For me, at twenty-two, this involved working in a bagel shop and spending a lot of time in Coyote Joe’s, my local watering hole—but despite my youthful excesses, I worked steadily at the novel I had in mind.

Sure, it was a sprawling epic—and sure, my reach exceeded my grasp (by a mile, at least!). But the book didn’t fail because I lacked vision, nor did it fail because I stopped writing—in fact, I worked diligently on it for the next ten years of my life.

That novel failed because every time something seemed off, I went back to the beginning and revised.

The Power of Deadlines

There is a perennial truth known to grad students and journalists: a looming deadline will make you actually finish a piece of writing, no matter how epic or ambitious your aims with it might be.

When I went back to school at thirty-two, I no longer had the luxury of revising ad infinitum, because I had to turn out twenty pages of new work every two weeks.

And yet, these were somewhat famous people I was working with, who might just give me a hand up if they liked my work. The incentive to produce polished prose was high.

But how could I produce polished work in just two weeks?

My solution was simple: I worked twelve-hour days. I hadn’t kicked my perfectionist’s habit of revising as I drafted, I’d just found a way to accommodate it (by eliminating nearly everything else of any consequence from my life).

As a result, I did produce some polished work (though I’d scrap a whole lot of it later; see Editor’s Note, below). And maybe, just maybe, I managed to impress someone—if not with my work, than my work ethic.

But what I lost, in the process, was my enjoyment in writing itself.

Remember When Writing Was Fun?

When I was a kid, I didn’t dread the act of writing. Between the pages of my composition notebooks, fantasy worlds came alive and “imaginary friends” became real. I was always looking for an excuse to play hooky from the rest of my life (especially if it involved homework or chores).

After grad school, I asked myself, “When did writing become something I hate?”

I realized this change occurred when I tried to perfect a piece of writing, to finish it, in too short a span of time. But that short span of time—the almighty deadline—was what had finally allowed me to finish in the first place.

How could I make writing fun again, while actually producing publishable work?

For me, the answer was this: Stop revising as you write. Separate drafting from revising. And reconsider your tools.

Part One: Stop Revising as You Write

Remember my Great (Unwritten) American Novel? It’s languishing in the back of my hard drive because I could not stop going back to the beginning and revising it. Which, though it gave me the illusion of progress, kept me from doing anything more than inching forward.

It can be useful now and then to look back at where you’ve been with your novel and the promises you’ve made to your reader—useful too to remember what the voice of the protagonist or narrator sounds like.

But take it from someone who sacrificed years of her life in the service of a failed manuscript: that boomerang that keeps sending you back to the beginning is unlikely to ever give you enough momentum to write your way through to the end.

And oftentimes it’s only once you’ve reached the end of your book that you know—really know—the way that it should begin. So no matter how polished your opening pages might be, you might have to scrap them in the end.

Part Two: Separate Drafting from Revising

When I talk about drafting, I’m talking about the process of creating new work. By revising, I’m talking about the process of improving that work—adding to it and deleting from it, reshaping and improving it.

Productivity experts tell us that we’re less efficient when we’re constantly switching between tasks, and it doesn’t take a neuroscientist to tell you that drafting and revising make use of very different parts of the brain. (The former generally involves throwing spaghetti at the wall; the latter involves deciding what sticks.)

As a consequence, switching back and forth between these two tasks in the same session tends to be not only inefficient but frustrating—and because it’s hard to do both tasks well, you never quite achieve the effortless state of flow.

That’s another term productivity gurus like to throw around. But writers, you know what I’m talking about: The flow state in drafting is when the next word, the next sentence, the next movement of the story, is clear; the flow state in revising is when you can easily tell what’s on and what’s off (and how to address the latter).

If you want to work efficiently—and with less frustration—my advice is to separate these two tasks as much as humanly possible.

Part Three: Reconsider Your Tools

When I decided I was going to make writing fun again, I tried all sorts of process-oriented hacks. Some of them stuck, and some of them didn’t, but one of the most useful strategies I found was drafting by hand.

When you open up a Word document, the first thing you see is the beginning of the piece. If you’re a perfectionist—and to succeed at writing, I believe, you must be—it’s difficult not to get sucked in. (What’s a little nip and tuck here and there?)

The trusty composition notebook from my childhood, I found, did not work that way. I opened to the last thing I had written, not the first—and in doing so, more effortlessly found the thread (especially if I had made a few notes the last time I wrote, about what came next).

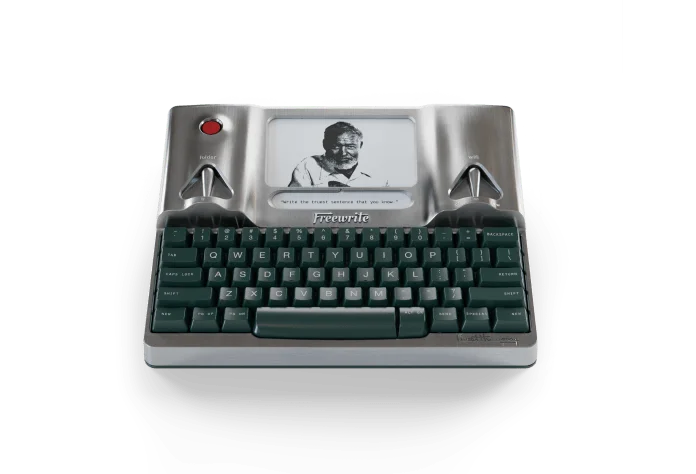

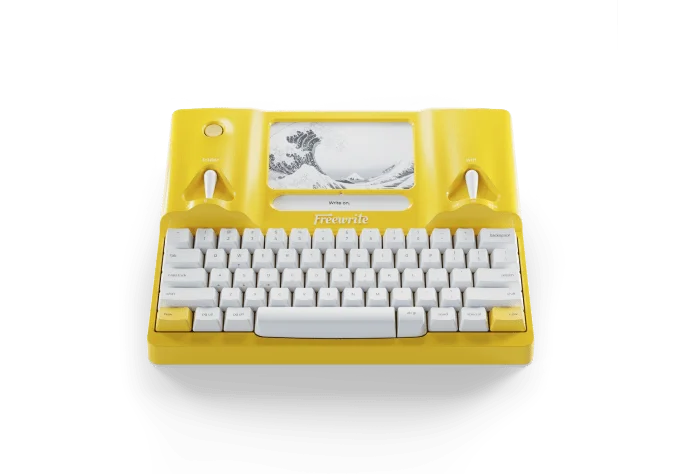

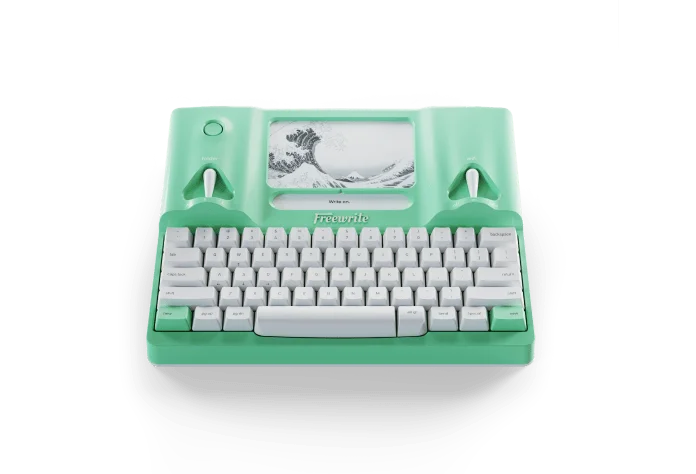

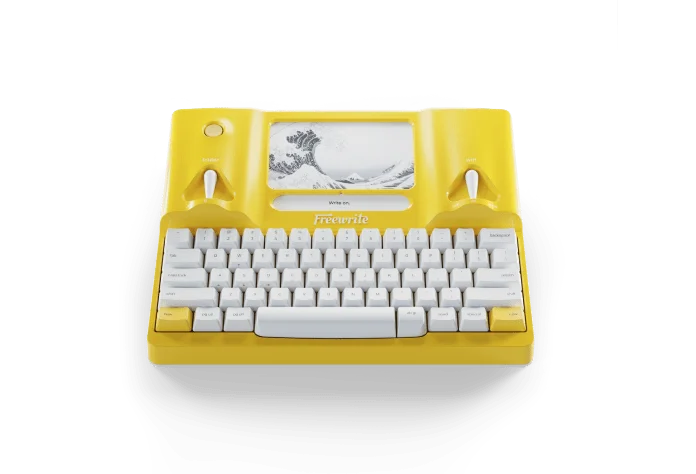

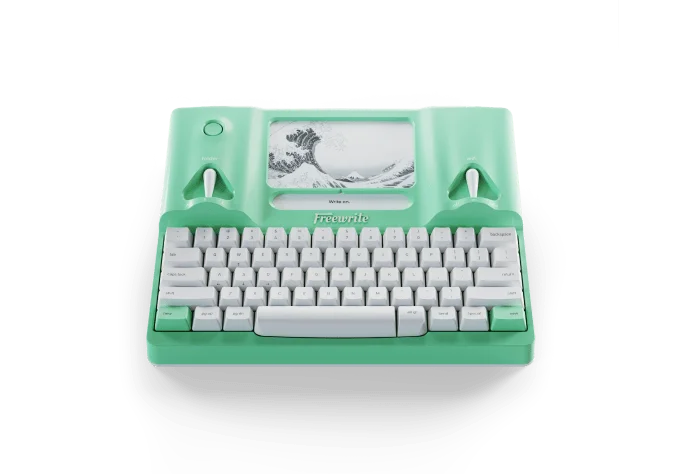

Of course, writing by hand is slower than writing on a computer. So if you can find a way to write—via a typewriter, via tech like the Freewrite, or simply via the willpower required to start at the end of your Word document, rather than the beginning—you’ll have the best of both worlds.

Editor’s Note

Everything I’ve learned in the course of my journey as a writer has been backed up by what I’ve learned in my career as a freelance book editor.

At Indigo Editing & Publications, we work with authors over the course of three distinct rounds of editing: a developmental edit, a line edit, and a proofread.

Which is to say, we don’t cut a comma, question a word choice, or ask to see a single image clarified until the story itself has been nailed down. Doing so would be a waste of the client’s money, and of our time—because the word, sentence, or image in question might not even make the cut for the next draft.

Just as writers are best served by separating drafting from revising, revising is best served by separating work on the story from work on the language itself. It can be hard to do, but it is, without a doubt, the most efficient way to work.

In Conclusion

Certainly, there are exceptions to every rule, and there are some successful authors who meticulously revise as they draft new work (Zadie Smith is a good example). But in my experience, these writers are the exception.

Those who succeed in publishing are usually those who’ve learned how to reliably enter a state of flow, in both drafting and revising—and in most cases, they’ve learned to do it by separating drafting from revising.

Of course, I’m curious about your thoughts on this. When has writing been the most fun for you? How has perfectionism served you as a writer (or held you back)? And what’s the number one most useful writing hack you’ve found?

An author, editor, and educator, Susan DeFreitas’s creative work has appeared in (or is forthcoming from) The Writer’s Chronicle, The Utne Reader, Story, Southwestern American Literature, and Weber—The Contemporary West, along with more than twenty other journals and anthologies. She is the author of the novel Hot Season (Harvard Square Editions), which won the 2017 Gold IPPY Award for Best Fiction of the Mountain West. She holds an MFA from Pacific University and lives in Portland, Oregon, where she serves as an editor with Indigo Editing & Publications.