Literary devices — specific creative writing techniques that have been in use for centuries by everyone from Charles Dickens to J. K. Rowling — have the power to take a piece of writing from mediocre to majestic. However, you need to know how to use literary devices if you want to avoid unintentional gaffes that drive your readers away.

If you’re a writer, you’re already using literary devices, even if you don’t realize it. Knowing how to use them well adds more impact to your story and makes for a more impactful narrative that your readers will appreciate.

There are dozens of different literary devices that you can manipulate in your writing — far too many to cover in-depth in this article. I will reveal my three favorite literary devices, with examples of how to use them.

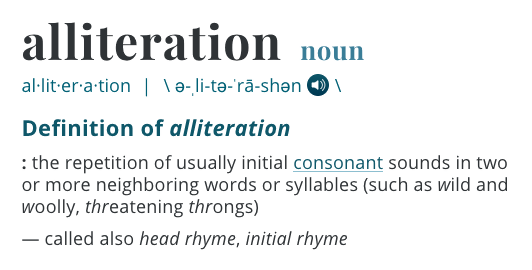

1. Alliteration

You remember alliteration from school, right? The technical definition of alliteration (according to the Merriam-Webster online dictionary) is:

By far, alliteration is my favorite literary device. I have to be careful not to use it too much if I’m honest. When you use one particular literary device too often, it can lose its power, so it’s important to get the balance right.

You find a lot of alliteration in nursery rhymes and book titles. Let’s look at some examples:

- Little Miss Moppet

- She sells seashells, sitting on the seashore

- Baa baa black sheep

- Betty Botter bought some butter

- How much wood would a woodchuck chuck; If a woodchuck would chuck wood? A woodchuck would chuck all the wood he could chuck; If a woodchuck would chuck wood

- Peter Pan (book by J. M. Barrie)

- The Two Towers (book two of The Lord of the Ringsby J. R. R. Tolkein)

- Nicholas Nickleby (book by Charles Dickens)

- Sense and Sensibilityand Pride and Prejudice (books by Jane Austen)

Alliteration isn’t just for rhymes and book titles, however. It can add impact to your writing, drawing your readers’ attention to sentences you want to emphasize. Phrases that include alliteration are more memorable.

Statistics say that you’re more likely to accurately remember (and recite) sentences and phrases that use alliteration even years later (Brooke Lea, et al., 2008). It’s one reason you often see alliteration used in marketing materials and brand names — such as PayPal, Coca-Cola, Dunkin’ Donuts,and Best Buy.

Alliteration can create mood and convey things like danger by merit of association. For example, repetition of the initial ‘s’ sound is associated with the slithering of a snake, implying danger:

Simon’s shoes slipped on the wet slope, and he began to slide towards the edge of the cliff. No matter how hard he tried, he just couldn’t regain his balance. An almost silent scream left his lips as he hurtled over the side.

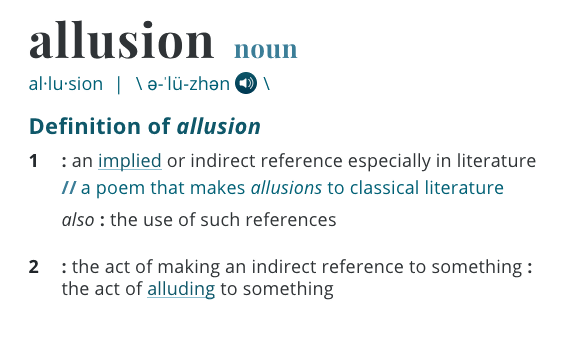

2. Allusion

Allusion is often confused with illusion — but they are very different things. Here’s how the Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines allusion:

Allusion allows you to paint a clear picture of a mood, character, setting and so on by referencing something your readers are likely to be familiar with (often a cultural or historical reference). By using allusion in your writing you can avoid lengthy and awkward descriptions.

However, allusion can backfire on you. That’s because not all cultural or historical references are ‘evergreen’. ‘Evergreen’ refers to things that are timeless. The problem is, you can’t guarantee that readers in ten years’ time will understand the same cultural references as your readers today.

Let’s look at some examples of how you might use allusion:

Kevin shrugged off the compliment. “I’m no Stephen King,” he chuckled. “I don’t think I will be topping the bestseller lists any time soon.”

- In this example, the character is comparing his writing abilities to the successful, prolific novelist Stephen King. This is a semi-evergreen allusion because it’s likely that people will understand the reference for a few decades at least, but there may still be some readers who aren’t familiar with the reference.

- This reference to Pandora’s Box is evergreen because most people will have at least some understanding of what ‘Pandora’s Box’ refers to.

- Biblical references like this are almost universally understood, making it possible to convey an image of the setting in a single phrase.

- You can convey a lot about a person by alluding to a historical figure who is well known for a particular set of characteristics.

I’ve seen other types of allusion where the reference is more of an inside joke, which risks alienating readers who don’t ‘get it’. Only use allusion when you’re certain that your audience will understand the references you’re making. Here are some examples of how allusion can go wrong.

“I felt sure the Cold War was over,” Patrick muttered, hitting the power button on the TV remote and slumping back in his chair. He didn’t know why he still put himself through the torture of watching the evening news anymore.- As a member of the millennial generation who grew up with Cold War references, I understand the allusion in this passage. However, younger — and future — generations won’t get it.

- In this passage, Patrick refers to the Cold War as a way of passing judgment about pointless bickering between politicians. If you don’t understand the cultural background of the Cold War — decades of “war” where no actual fighting happened and very little was achieved — then this passage is meaningless.

- I worked for a while in the bookselling industry and I’m a writer, so I get what the author is trying to allude to in this sentence — but it’s very much an inside joke that could make readers feel that the author is excluding them.

- Bestselling author James Patterson is well known for churning out several books every year — and Rick’s allusion to Patterson here is a defensive remark that hinges on the reader understanding that the secret of Patterson’s prolific publishing schedule is that many of his books are ghostwritten by other authors.

3. Personification

How does the Merriam-Webster Dictionary define personification?

Personification, in fiction or poetry, is the act of describing objects, thoughts, and concepts as if they have human qualities. It’s a powerful technique that can give your readers a means of visualizing or understanding abstract things in a more concrete way. Effectively, it’s like you, as the author, are reaching out of the page and pulling your readers into the midst of your story world.

In addition, personification allows you to direct your readers to a specific interpretation, understanding or perspective on something. This is particularly true if you avoid popular (or overused) types of personification (such as “Mother Nature holds the cards” when describing the unpredictable nature of weather) and instead offer something fresher and unique:

Tony laughed as he watched the weather forecast. “Glad I’m not going on the camping trip this year,” he announced to the empty room. “Seems like Mother Nature’s giving out the punishment homo sapiens deserve for being so destructive. Not before time, either. If the human race was my kids, I’d have given them hell before they completely destroyed the world.

When it’s done well, personification is powerful. Let’s look at some examples, and why they work so well.

-

My laptop threw a tantrum and refused to cooperate.

- Describing an inanimate object like a computer in terms you’d use to describe a toddler has the effect of making the character’s struggle relatable and conveying the character’s frustration with the machine. This sentence is dramatic — but anyone who uses computers will get how the machines often seem to have a mind of their own.

-

The vicious tornado screamed in fury as it rampaged through the town, tearing off roofs and carelessly casting them aside.

- You could write this sentence without the personification: “The tornado blew off dozens of roofs.” However, you can visualize the scene more strongly with the aid of personification. It adds power and impact to the sentence, taking it from bland to enthralling.

You have to be careful with personification, however. Sometimes it just doesn’t have the same impact:

-

Jessica sighed. The cat just would not cooperate.

- Technically, this is personification, since it’s attributing the human quality of cooperation to an animal. However, cats and dogs are commonly seen as having human qualities anyway, so this example of personification doesn’t add power or impact — it’s more of a statement, in the same way as if the sentence read, “Her son just would not cooperate.”

Using Literary Devices in Your Writing

If you want to take your writing to the next level, you need to use literary devices. I’ve only covered three in this article, but there are many more that you can explore. Literary devices enable you to control how your readers interpret scenes that could have multiple interpretations, add visual power to your paragraphs, and draw your readers deeper into your story world.

I’ll be doing a part two to this article, looking at less well-known literary devices like Anaphora, Epistrophe, Chiasmum, and Hypophora. Comment below if there are other literary devices you’d like me to cover in-depth. I’ll leave you with some practical exercises that will help you bring literary devices to life in your writing.

Practical Exercises

- Pick a scene in your current writing project and experiment with using alliteration to draw attention to important phrases. I’ve found that adding alliteration during the editing process is more effective. You should also look out for how your favorite authors use alliteration in their novels. Notice how the alliteration affects you as you’re reading.

- Find a passage in a piece of your writing where you describe a character’s nature. Can you think of a cultural or historical person who embodies those characteristics and your readers will recognize? Re-write the passage using an allusion to that person and see how that changes the impact of the scene. Repeat this exercise for scenes where you could describe a setting by alluding to a well-known place, or a situation where you could allude to a historical event that it compares to.

-

Here’s a list of overused examples of personification. Try taking the concept behind the example (as I showed with the Mother Nature example) and creating something new and unique using personification.

- Spring has no intention of arriving any time soon.

- Look at my car. She is a beauty, isn’t she?

- The wind whispered through dry grass.

- The flowers danced in the gentle breeze.

- Time and tide wait for none.

- The fire swallowed the entire forest.

- The windows in the empty house glared at us.

- The trees stood to attention.

- Lightning danced across the sky.

- The wind howled in the night.

- The approaching car's headlights winked at me.

- The camera loves her since she is so pretty.

- The stairs groaned as we walked on them.

- The leaves waved in the wind.

- Time flies when you're having fun.

- My flowers were begging for water.

- The ivy wove its fingers around the fence.

- The thunder was grumbling in the distance.

References

- Brooke Lea, David N. Rapp, Andrew Elfenbein, Aaron D. Mitchel, Russell Swinburne Romine (2008). Sweet Silent Thought: Alliteration and Resonance in Poetry Comprehension Psychological Science, 19 (7), 709-716 DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02146.x